An essential requirement for a species is that they can reproduce and have fertile offspring. Clearly if they cannot do so, they become extinct.

Most hybrids such as a liger, which results when a lion and a tiger mate, are infertile. The same occurs when a horse is cross-bred with a donkey, producing a mule, or a horse and a zebra. Neither a liger nor a mule are considered species, but lion, tiger, horse and donkey all are separate species.

This definition of a species is not sacrosanct. Many species, such as those that have evolved on islands or other cut-off environments, appear distinct, and are considered separate species. However if you transported them elsewhere they may be able to cross-breed, producing fertile hybrids. If the genetic advantages of the hybrid were greater than the parents’, it would be possible for a new species to evolve. Interestingly, even though Arabian camels and llamas are different species, they have the exact same number of chromosomes, and fertile cama have resulted from this union. If these cama were bred, a new (Man made) species could result.

In the past species were determined if they couldn’t interbreed with close relatives, by any anatomical differences, and by their behaviour. Through most of my guiding career, the giraffe has been considered one species (Giraffa camelopardalis) with several sub-species. However some of these sub-species appear very different, and a feature of visiting some areas has been to see a variety of giraffe. Why, if they are so different, have they been considered only one species? It may be because in the areas where two sub-species overlap, a mix of features often results. These days genetic analysis is playing a huge part in determining species.

Recently Nature published an article from a genetic study of giraffes stating that there are actually four distinct species of giraffes in Africa – the southern giraffe (G. giraffa), found mainly in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana; the Masai giraffe (G. tippelskirchi) of Tanzania, Kenya and Zambia; the reticulated giraffe (G. reticulata) found mainly in Kenya, Somalia and southern Ethiopia; and the northern or Nubian giraffe (G. camelopardalis), found in scattered groups in the central and north-eastern parts of the continent.

So the world population of about 550 Thornicroft’s giraffe that is only found in Zambia’s Luangwa Valley, and which through its isolation would seem that it must be distinct from any other giraffe, is actually now considered a population of Masai giraffe (G. tippelskirchi).

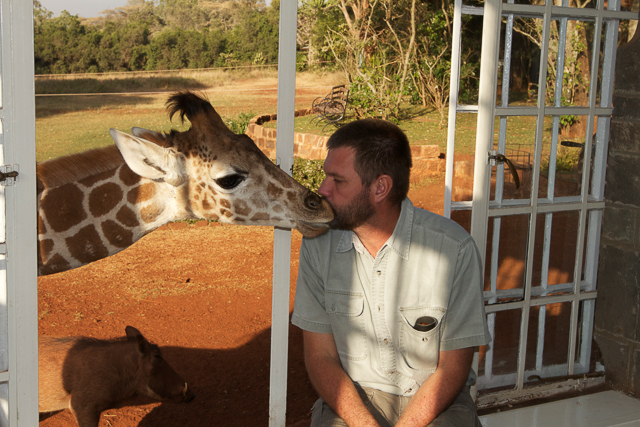

The equally unusual Rothschild’s giraffe that always seemed distinct from the other two Kenyan giraffes – the Masai giraffe (G. tippelskirchi) and the Reticulated giraffe (G. reticulata) is indeed distinct from them, but is not its own species. It is officially a variant of the Nubian giraffe (G. camelopardalis). There are only about 1,500 Rothschild giraffe remaining in western Kenya and in Uganda. One of the most well-known giraffes was a Rothschild giraffe called “Daisy” cared for on a country estate in a suburb of Kenya’s capital Nairobi and who features in the book “Raising Daisy Rothschild” (ISBN-10: 0446899488).

Hopefully the fact that there are more Nubian giraffes other than the Rothschild’s variety scattered across the northern part of the African continent, and that there are more Masai giraffe in eastern Africa other than the Thornicroft’s giraffe will not lead to less effort being taken to protect them, as whatever the scientists say – they are wonderfully special!

Justin